Journal Date: February 2, 2021

The second practice Estés recommends in Warming the Stone Child is this:

“Remember back to childhood, your favorite fairytale, and consider that that fairytale actually became your myth, the guiding light of your life. And if that fairytale had a really rotten negative ending on the end of it, then you may wish to choose a new ending. You may wish to actually sit down and write, to play, to act, to mask-make, to dance a new ending to that fairytale. If the fairytale had a positive ending, then see what you can do to live that out. See what you can do to make that true in your own life.”

When I heard this, I didn’t have to think twice, I knew immediately exactly what my two myths were.

I’ll start with the more difficult of the two first.

When I was in high school, I loved literature about tragic women.

The stories I loved were always about women who dared to resist the rules and limitations placed upon them. They were women who paid dearly for it, each of them ultimately paying the greatest price of all in the end.

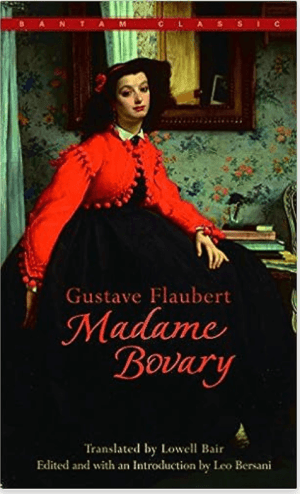

Yes, Anna Karenina, Madame Bovary, and Edna (from Kate Chopin’s The Awakening) all paid for the price of their liberation with their lives. Sadly, each one committed suicide before the novel was over.

Each had left their stifled, boring and restrictive roles as wives and mothers, left to look for true love and sincere pleasure.

And each of them was punished greatly for it. There could be no other ending for any of them, it seems.

I, too, felt myself involved in a struggle for my own life.

I, too, wanted to reclaim my existence for myself, to wrench my destiny out of the hands of society, and claim myself for me.

Clearly, I identified with these women who felt trapped in their given roles.

What I failed to see was the moral lesson these stories now seem intended to impart.

I’d always thought the authors had portrayed these women sympathetically.

And yet, each of them had sentenced their protagonists to an early death.

Each died by her own hand for having disobeyed the laws of the land, the unwritten laws that required women to be docile, submissive, and in never-ending servitude to children and to men.

It seems to me now that these were in fact cautionary tales. While they depicted an alternative route a woman could take, it warned us all that it was only a dangerous dead end to be avoided.

They seemed to say, “Don’t ask questions. Don’t get any ideas. Don’t stray, or else.”

It took me years to realize I’d internalized these stories about women and what we deserved.

And to recognize that I had been living them out myself, in my own way.

I too felt that I had strayed. That I had chosen myself and my own desires over what men or the world wanted for me as a woman.

And I could, even now, feel the specter of death lingering near me.

For so many years, I suffered under the weight of feeling I had gone too far, that all hope was gone, and that death, yes, my own death, by my own hand, was the only “honorable” and “right” resolution to this story I was living.

Now that I see this, I’m ready to let it go.

Now I am willing to release this internalized demand for punishment, this death wish that exists for women who dare to belong to themselves.

In all honesty, I struggle even now to imagine a different outcome for any of the women from these novels of the 19th century. I don’t know if much else would have been possible, at least, without having these women face some other equally awful consequence.

But I don’t need to redeem them.

It is me, a woman living right now, that requires redemption.

And not through punishment or penitence.

No, the way I will tell my story from now on, those things aren’t required.

So what happens at the end of this story?

In this version, the woman realizes she had the right idea.

She has not only a right, but a responsibility, to belong to herself. To live her own life, for herself, as she sees fit.

This doesn’t have to mean choosing one of the two standard options offered to us. There are more choices to be had than blind submission or careless rebellion.

I can choose instead to live with integrity, to honor myself without putting myself in dangerous situations.

I can now choose a life that truly benefits me, because I finally believe that I have a right to.